So we’ve all been there – or at least I’d like to think so. You’re traveling to somewhere far away, or perhaps doing the reverse journey back home, and the thought crosses your mind:

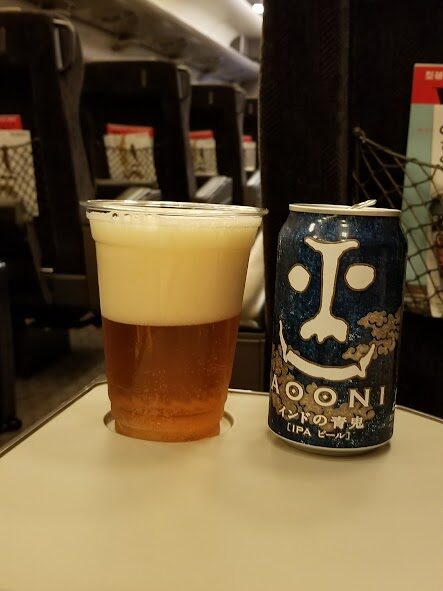

“A couple of cold beers on that long shinkansen ride would make this journey infinitely better.”

Whether you’re seated in the green car with extra legroom, or squeezed into a night bus bound for Kyushu, the idea is the same. The miles will roll by more easily with a can or two in hand. Of course, it’s not just the beer itself – it’s the whole ritual: sipping something bitter to balance those salty travel snacks. Maybe it’s fish bones from a local souvenir shop, maybe it’s a bag of crisps from the convenience store. Perhaps you’d even prefer something malty to soften the edges of a long day.

Stations and Craft Beer : Table of Contents

The Convenience Store Fridge: A Familiar Yet Predictable Sight

You make your way into the station’s konbini, or perhaps the local souvenir shop hawking regional knick-knacks. Keychains shaped like mascots, socks printed with prefectural flowers, maybe even the ubiquitous clear plastic A4 files featuring cheerful illustrations of local produce. But then – there it is, glowing like a beacon – the cold fridge full of drinks.

And here comes the disappointment. Asahi? Check. Sapporo? Check. Kirin? Check. Suntory? Of course. Row after row of macro lagers, neatly chilled and reliable, plus their chu-hi cousins and whisky highballs. You scan the shelves again, shifting cans aside, hoping for a miracle. But the miracle rarely comes. No local IPA from the prefecture you just visited, no saison from a nearby mountainside brewery. Just the same big brands you could buy at any station across the country.

Exceptions That Prove the Rule

Over the years, I’ve taken the shinkansen countless times – from Tokyo down through Nagoya, Osaka, Himeji, Okayama, and even as far as Fukuoka. These are major hubs, each serving thousands of passengers every day. You’d think, if anywhere, they’d be prime places to showcase local brews. But no. Instead, you’ll mostly find the same familiar macros and maybe a limited-edition lager with a seasonal cherry blossom printed on the can.

There are, however, rare exceptions. Shin-Kobe station, for example, has been known to stock beers from Rokko Brewing. Are they the best beers you’ll ever drink? Probably not. But when you’re standing there in front of the fridge, about to board a train, the sight of a locally brewed saison feels like a small victory.

Shin-Yokohama sometimes stocks offerings from TDM 1874 Brewery, though availability is inconsistent – sometimes the shelves are full, other times wiped clean. Tokyo station maybe has a few bottles of beer from Hitachino Nest if you’re lucky.

Echigo-Yuzawa, a station in Niigata famed for its sake, actually does a great job of offering local craft beers alongside regional nihonshu. Kanazawa, too, gives travellers a chance to sample craft from Ishikawa. But beyond these exceptions, the rule is clear: craft beer in train stations remains scarce.

Why Craft Beer Is Hard to Find in Stations

So why is this the case? After all, Japan has over 500 craft breweries, and more seem to appear each year. Wouldn’t it make sense for stations – those bustling gateways between prefectures – to showcase local pride through beer? The reasons are layered, but I’d put them into three main categories:

1) Market Size and Demand

As of 2024, craft beer accounted for just 0.95% of the Japanese beer market, up from 0.72% in 2019. It’s growth, yes, but still tiny compared to countries like the U.S., where craft regularly exceeds 12–15%. For many shops, stocking shelf space with craft beer simply doesn’t seem worth the risk. Most consumers heading for the train want a safe, familiar choice. Macro lager is the default: cheap, refreshing, consistent.

2) Production Limitations

Even if the demand were there, supply might not keep up. Many Japanese craft breweries operate in small facilities, often converted from old warehouses or tucked away in rural areas. Expansion is costly and risky. A brewery can’t just magically add another fermentation tank without space, money, and confidence that the beer will sell. For convenience stores inside busy stations, the last thing they want is a product that might be hard to restock or inconsistent in availability.

3) Shelf Space, Shelf Life, and Risk

Here’s the harshest reality: macro beers are pasteurized and built to last. Their shelf life can stretch close to a year without noticeable decline. Craft beer, on the other hand, is more fragile. A hoppy IPA might taste best within two to four weeks of packaging. Even malt-forward styles rarely last beyond six months. For a shop manager, that’s a gamble. If the beers don’t sell quickly, they either sit and deteriorate – risking a bad consumer experience – or they’re sold off at a loss. Neither scenario encourages repeat stocking.

From the store’s perspective, filling valuable fridge space with something reliable, familiar, and long-lasting makes far more sense.

A Missed Opportunity

And yet, it feels like a missed opportunity. Japan’s regions are proud of their local produce – stations overflow with souvenir sweets, pickled vegetables, regional bentos, and bottles of sake. Why not extend that same pride to craft beer? Imagine picking up a can of Hiroshima pale ale while passing through, or grabbing a Wakayama fruit saison to drink on the ride home. The infrastructure for showcasing regional specialties is already there – craft beer simply hasn’t been invited to the party yet.

Signs of Hope

That said, the situation is improving slowly. Breweries are forming stronger partnerships with JR companies and local tourism boards. Regional craft fairs and pop-up kiosks sometimes appear inside stations during holidays. The growing number of inbound tourists, many of whom actively seek out Japanese craft beer, is also creating pressure to expand offerings. If Echigo-Yuzawa and Kanazawa can make it work, perhaps other major stations will follow.

For now, the dream of easily grabbing a fresh local IPA on your way to the shinkansen remains more fantasy than reality. You’ll most likely end up with an Asahi Super Dry or Kirin Ichiban – dependable companions for any journey. But the craft beer scene in Japan is evolving, and with it, the hope that one day train station fridges across the country might tell a richer story: not just of national beer giants, but of the small, inventive breweries tucked away in the prefectures you’re traveling through.

Until then, if you’re serious about craft beer, the best strategy is simple: plan ahead, buy local at the source, and carry a few cans with you to the station. That way, when the train pulls out and the snacks are opened, you’ll have the beer you were truly hoping for.